Orphan Hojuk (Family Register)

The orphan hojuk or family register was the first document created by Eastern to make me legally adoptable.

It was created when I was six weeks old.

The primary purpose of the hojuk for non-adopted Koreans was to record one’s relationship to their family, noting in particular that family’s geographical ancestral origin. Every Korean person (before 2008) was theoretically recorded on a hojuk. *In 2005, the Constitutional Court declared the hoju system to be unconstitutional because of its inconsistency with rights to gender equality and individual dignity, guaranteed in the Constitution. The system was abolished in 2008.

It was possible to create a new hojuk in circumstances, such as, when a son got married and was therefore starting a “new household” or where a non-Korean (without a Korean father) became naturalised or when a North Korean defected to South Korea and assumed a legal identity in the South, for example. The practice of creating a new hojuk was very normal. But creating a hojuk for the purposes of sending children overseas indefinitely was not normal. Until it was.

The hoju system was deeply patriarchal in that a woman could not be the hoju, the “head” of a household. She could not hold her own hojuk. She would always be on her father’s or husband’s hojuk. However, an exception to this rule was when establishing a new hojuk, as was the case for adoptees and their orphan hojuk.

The adoption agencies needed adoptees to have a hojuk, which provided the basis for our legal identity, so they could apply for our travel documents - a Korean Passport and a Visa for our adoptive countries - to leave Korea.

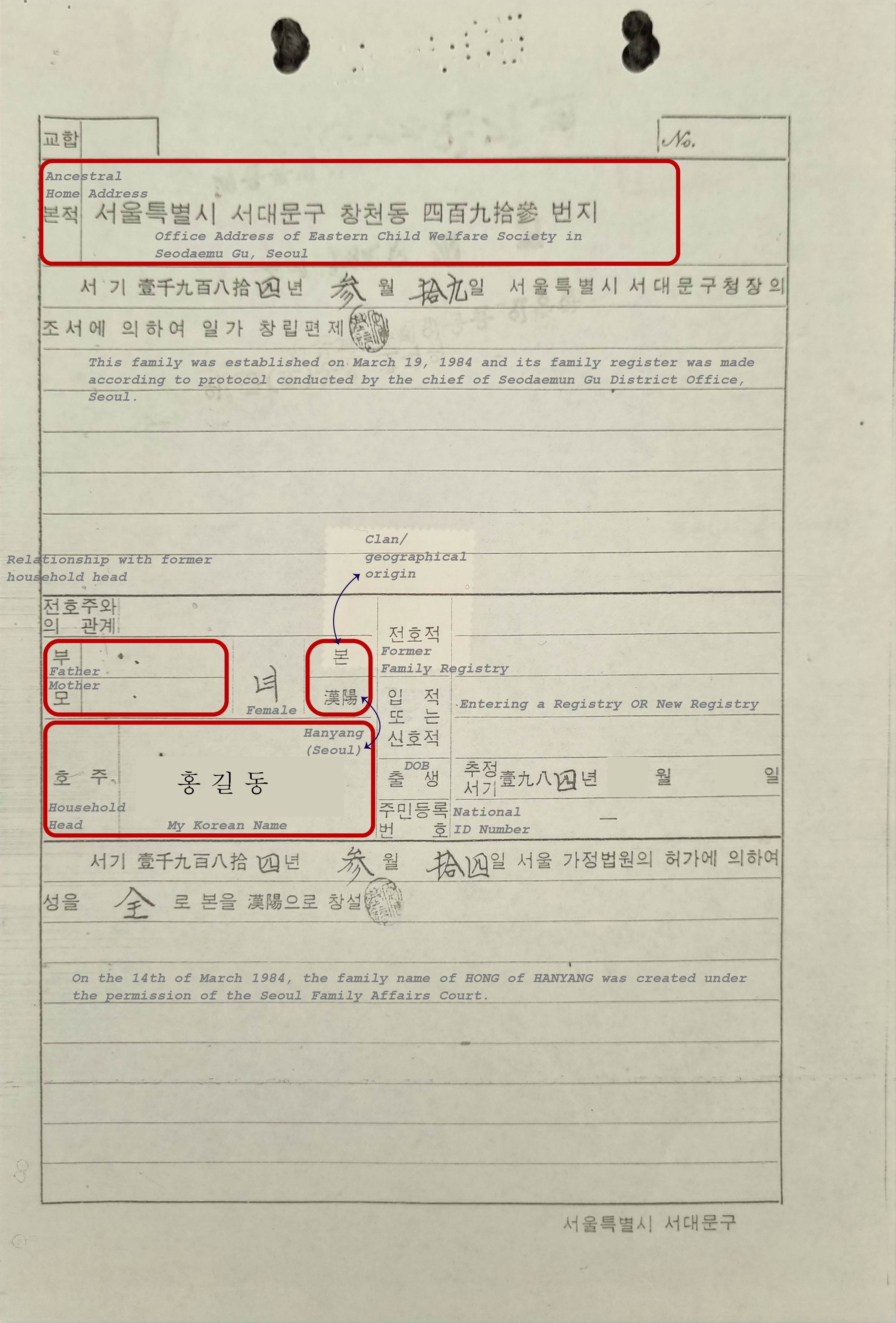

A copy of my orphan hojuk in Korean (with anonymised name and translations of the Korean text)

English translation of my orphan hojuk. The yellow represents all the fields that were left blank on the Korean original and the use of the fabricated Hanyang bonjuk.

As mentioned, the primary purpose of the hojuk for a non-adopted Korean person was to record their relationship to the male family head. In a cruel irony, the adoption agencies repurposed the hojuk with the effect of completely severing the relationship between an adoptee and their family and to fabricate their ancestral origin.

The orphan hojuk created each of us as a lone individual, the head of our own “clan” without ties or roots or relatives. It was an easy and straightforward way to get us adoption-ready.

*Some adopted people were entered on the family register of their birth family before they were relinquished or otherwise taken from their family. This means that they exist as two different legal people in Korea - the child of their birth family AND as an abandoned orphan. It was the abandoned orphan identity that the agencies used in the adoption process.

Empty Words on a Heavy Document

For many adoptees, their orphan hojuk is one of the few documents from Korea, which on its face appears to give information about our identity or birth family.

But it is a complete fabrication. The information on an orphan hojuk is made up and useless for the purposes of birth family search because it bears no connection to our actual birth families.

There are some details on the hojuk that adoptees sadly construe as pertinent and personal to them, but which are actually generic and seen widely across all orphan hojuk.

Every hojuk mentions the family head’s bon kwan 본관. The bon kwan is something similar to a clan - a large extended family, all supposedly descended from one man who lived in a specific place in Korea. This place, along with their family name, passed down, generation to generation from that one originating man was written on every descendant man’s hojuk. The bon kwan was an important way to distinguish families who had the same name. For example, there are many Koreans with the last name Kim. They can know from their bon kwan if they are from the same patrilineal line or from different families.

The word 본관 bon kwan in most English translations becomes “Family Origin.”

The adoption agencies needed to create a clean administrative start for us. So they fabricated a new hojuk and made each adoptee the head of their own “clan.” For many adoptees, the adoption agency made our names up. And even if known, our bon kwan was also made up. We were given a new bon kwan which, for many, was the geographical location of the adoption agency office. For all four agencies, this was Seoul. Perhaps to give the designation an air of old-timey authenticity, they changed the fake bon kwan from the city’s modern name, Seoul, to its old one, Hanyang. For this reason, many adoptees will see the words “Family Origin: Hanyang” on their hojuk. This is not a truthful expression of the person’s own origin nor does it bear any connection to their birth family.

I have seen bon kwan other than “Hanyang” on some orphan hojuk. For example, Milyang for those with the family name Park or Gimhae for Kim or Jeonju for Lee. It is unknown how the agency workers were selecting the bon kwan and if they were in fact all made up or if they sometimes used the real name and bon kwan of one of the adoptee’s birth parents. However, when other documents in the file give no other information about the birth family, the scant details such as those found on a hojuk are useless for the purposes of birth family search.

The hojuk was the legal foundation upon which adoption agencies were able to designate us as parent-less orphans, ready for adoption. It created a fiction of our origins - one with no parents and no origin.

In my case, something that bothers me is the very clear inconsistency between the information given on my Initial Social History and on my hojuk about my birth parents. In the English translation of my hojuk, the word “NONE” is written for my birth mother and father. Yet my Initial Social History gives the names of both my parents and their ages. Even if the Australian social workers had no understanding for why the hojuk existed, this considerable discrepancy should have raise red flags for them when looking at my documents. And it was not just me. There were hundreds of Korean babies being processed in the same way. Many of us had a similar story about why we were given up for adoption. Then we had a document that said our parents were “NONE” and (for many of us) another document that clearly stated their name(s). This inconsistency in two of only a handful of documents that came from Korea should have been a cause for alarm.